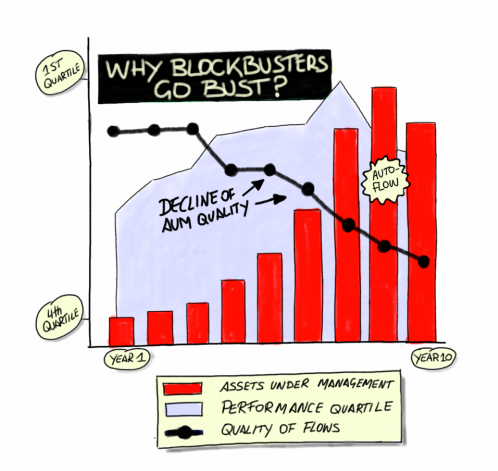

Why blockbusters go bust

One of the biggest killers of successful asset management companies is too much money flowing into too few products* too quickly. When things go awry, unsuspecting investors in those products are the ones left holding the bag. The industry is riddled with the fragments of once big, seemingly unstoppable, blockbusters that have taken on more than they can handle.

Along with factors such as ownership changes, personnel departures and style drift, asset bloat is a serious problem. In fact, I would argue, it is the primary driver of many other problems that fester as a product grows. Nothing has greater implications on the future ability to sustainably manage investments going forward than flows in and out. Asset size changes everything: people, process, philosophy, liquidity, risk – a whole range of crucial due diligence focus areas. Monitoring the growth and its potential impact to an investment product is key in proper due diligence. A lot can happen from the initial point of investment and the exit.

Of course, there is a certain comfort that comes with investing with the crowd through big, well-known products – particularly when solid returns are being produced. But the risks in doing so are often underestimated and misunderstood. It is not simply the amount of money gathered but the quality. How do we understand quality? In a nutshell, the more knowledgeable and informed investors are, the more reasonable their expectations and tolerance for variability of returns. If investments are made based on the last couple of years performance and a shiny marketing brochure alone, quality is defined as low. Easy come, easy go. Higher quality assets stay invested and thus demonstrate better results for investors and asset managers alike. Sustainable large AuM levels are built on high quality asset bases.

Quality has a lot to do with the ‘intellectual commitment’ level of investors. As investment products swell in size, particularly in the late stage of the growth cycle, the average quality of assets tend to decline. This process often creates fragile and unstable situations within a manager and product and ultimately lead to busts.

The demise of asset managers and the blockbuster investment products that propelled their (short-lived) success are well-documented. Ex-post, the reasons appear so clear: market shifts, hubris, greed, lack of planning, mistaking talent for luck, performance falling apart, manager loosing his/her way, not foreseeing evolving trends and insular firm-level thinking all are influencing factors. But what is equally important (and at fault) are the decision making processes of investors who themselves contribute the blocks of money to create a blockbuster.

With skepticism riding shotgun, let’s think through how blockbuster products reach stratospheric status and then quickly come back to Earth – both at the hands of the investors who were responsible for the massive flows that built them.

As time progresses, there tends to be a cruel relationship between the quality and the volume of flows into a given investment product. Volume of flows goes up while the quality of flows goes down.

Here is a growing list of factors to consider:

The difference in quality and quantity of AuM is important and too often not understood and/or paid attention to – by either investors in the products or the asset managers who manage them.

We use the term ‘quality’ to denote those assets which are invested based on a substantially robust due diligence process and therefore understanding and intellectual commitment to the investment strategies’ characteristics, philosophy and process. Simply stated, high quality AuM is the opposite of hot money blindly chasing good past performance.

In the world of active, limited capacity management, as a fund grows in size, (from $1 -$25 billion in AuM for instance), the ‘late stage’ investments are generally less knowledgeable, less seasoned and therefore less ‘patient’ than the earliest investments.

Low quality assets might in fact be viewed as a liability for a manager in environments lacking liquidity or in which large flows create outsized cash positions that can be a drag on performance.

Generally, forward potential out performance becomes increasingly reduced (due to compression of alpha-potential) as time progresses and asset size grows all the while, money continues to flow in blindly seeking those opportunities.

Coincidentally, the lowest quality assets have tremendous implications on the problems faced by an investment products in net redemption’s due to what we might term as an AuM fragility function. This is particularly true in narrowing liquidity environments.

Under the following assumptions: performance remains at a consistently high ranking (say 1st-2nd quartile) over the crucial evaluation periods (12 & 36 months), there is often an intermediate term influx period when the quantity of assets increases while the quality of the assets declines – both at an accelerating rate. At this point, the fund as a ‘default option’ may enjoy (and then suffer from) the autoflow function.

In an odd twist, the intermediaries who act as leverage points for distribution (global consultants, global financial institutions, etc.) have completed their work during their initial investment stage. Once ‘approved’ or on the ‘list’, the manager slips to ‘monitoring phase’ with a primary focus moving from process to results. Quite simply, the amount of qualitative and operational due diligence performed tends to be reduced at a rate relative to how ‘established’ a fund is.

Strong performance (even moderate performance following a sufficiently long period once an initial recommendation has been made) perpetuates flows – this we have labeled as part of the ‘auto-flow’ function. Turning off or slowing these flows present considerable challenges but necessary to preserve the integrity of the investment product and investors.

In the event of market turmoil, or poor performance of the investment product, outflows from investment products generally follow the LIFO (last in first out) accounting rule. That is, the lowest ‘quality’ assets, are the first to leave. It is equally important to recognise that late stage investors do not enjoy a cumulative strong performance record. They do not have the benefit of ‘playing with the house’s money’. This is exacerbated with illiquidity and market shifts (asset allocation away from fixed income to equity for instance…)

There are clear implications of a blockbuster on non-direct investment functions within an asset manager. Further, as the fund grows in size, too commonly the necessary support functions needed to maintain the health of the larger structure remain sub-scale – operations, administration, risk management, client servicing. Blockbusters also have important implications for sales functions within asset managers – particularly those paid on a ‘gross sales’ basis.

These factors are inter-related and have causal relationships.

* Here, Roland is addressing the environment for actively managed investment strategies and products. Given the shape and direction of the industry, it is important to consider the impact of AuM and growth rates on passively managed strategies – do products and the investors in them escape the risks inherent in active products?

This article is a revision of one Roland wrote ~6 years ago… these themes are still ones that regularly come up in my discussions with manager research analysts.

- Operations

- Due Diligence